Nails are common finds on historical archaeological sites in Ontario, including both nails for construction and those used to shoe horses- like the example depicted here. Aside from representing the activity of shoeing a horse, the presence of a large quantity of horseshoe nails can help determine patterns of use on a site. This is the case with horseshoe nails from the Kilmanagh Crossroads blacksmith site, where horseshoe nails gave key insights into how the smithy was organized.

Background on the Kilmanaugh Crossroads Site

Archival research showed that part of the Kilmanagh property was occupied by different craftsmen between 1857 and 1908. This included at least two successive blacksmiths. The first was R. Wylie, an English-born blacksmith, listed in the 1871 census as owning the property, which he bought in 1862. In the 1876 Assessment, W. McKenna was listed as a blacksmith of Irish descent on the property, which he bought in 1871. McKenna sold the lot in 1882 and by the time of the 1901 census, there is no further mention of a smithy. At this time, the only commercial lot on the property was a shoemaker. By the 1920s, a new domestic structure was built on the former smithy lot (ASI 2013:2,38). Despite having records that at least two blacksmiths lived and worked on this property during the 19th century, the location of the smithy was not known at the time of the archaeological investigation.

Almost 59,000 artifacts dated to between the 1850s and the 1890s were recovered during the Stage 4 excavation. They can be attributed to the activities of the Wylie and McKenna families on the property, although there is no distinct difference in the assemblage between these two occupations (ASI 2013:38). A root cellar was also discovered on the site and was interpreted as the location of the house where the smith and his family lived. It was typical at the time for rural craftsmen to live where they worked (ASI 2013:40). Although physical evidence of the blacksmith’s house was found, there were no obvious features that could be attributed to the smith’s shop and forge.

Analysing the Horseshoe Nail Distribution

Blacksmith shops were vital to communities that relied on horses, hand tools, and forged domestic hardware, and most general blacksmiths during the 19th century also acted as farriers (Doroszenko and Light 1997:67). A farrier is a craftsman who shoes horses and trims and cleans their hooves. Archaeological evidence supports accounts of the dual role for smiths during this era. The Kilmanagh Crossroads artifact assemblage included specialised tools related to blacksmithing and several horse related items: horseshoes, shoeing tools, and livery related items, but horseshoe nails were the predominant artifact type associated with blacksmith work discovered at the site (ASI 2013:33,35). The site had an unusually large quantity of horseshoe nails: more than 20,000 were recovered, making up almost 35% of the entire artifact assemblage. The points of most of these nails (96%) had been clipped off (ASI 2013:40). Complete nails represent those that are unused and clipped nails are indicative of use. When a nail is clipped, it leaves a protrusion that forms the clinch that is cut off or straightened when a horseshoe nail is removed during the shoeing process.

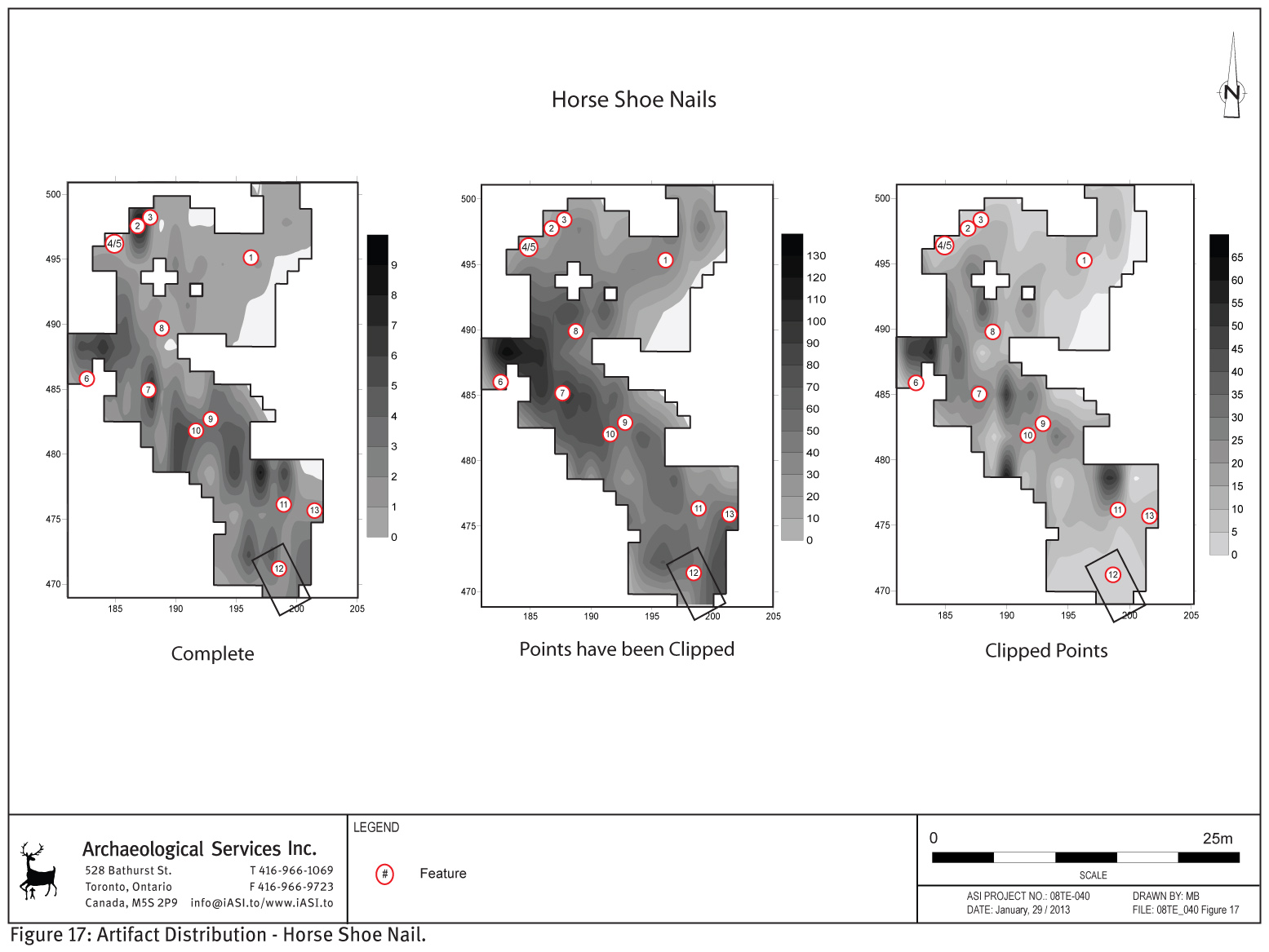

While writing the Stage 4 excavation report, Miranda Brunton became interested in the artifact distribution patterns of different artifact types, but especially horseshoe nails, and mapped them out to help locate the smithy (ASI 2013:Figures 16, 17). Artifact patterning is a useful interpretive tool for determining historic site function in archaeological investigations (Ball 1999). She determined that complete horse nails were found in multiple small clusters, but did not suggest a specific area of concentration. Nails with their points clipped were found across the site in large numbers, with a major cluster in two areas. Clipped points were found in four small clusters and one of these coincided with the major cluster of nails with clipped points. Based on the distribution patterns of these different parts of the nail – especially the overlapping cluster of a large quantity of used nails – the likely location of a main area for shoeing was found (ASI 2013:32-3). Miranda presented these findings in a paper written for a session on “Small Finds” at the Society for Historical Archaeology conference when it was held in Québec City (Brunton 2014).

A shoeing area is characterized by the presence of numerous clipped and clenched horseshoe nails, combined with the occasional new nail (dropped during the shoeing process) and bits of broken horseshoe that were left where discarded. These accumulate after repeated shoeing has occurred. This is because when an animal is shod, a new nail is driven through the shoe and hoof until the nail protrudes through the upper side of the hoof, where it is clenched down to hold the shoe in place. The excess nail is then clipped off (Light and Unglik 1987). If this concentrated pattern is found on an archaeological site, it might indicate the location where the activity took place.

An area where shoeing occurred was also thought to represent the entrance to a blacksmith shop. The reason being that since a horse was usually too large to bring into a forge, they were typically shod in front, near the entrance (Light and Unglik 1987:33). In the case of the Kilmanagh Crossroads site, the area interpreted as the location of repeated shoeing activity, which was also thought to represent the smithy shop entrance, was close to the road. The site was described as functioning as a commercial blacksmithing enterprise during the mid-to-late 19th century; and one which had direct access from the road (ASI 2013:40).

The large volume of horseshoe nails was also used to estimate the number of horses the blacksmiths might have shod. Assuming all horseshoe nails would be replaced at once, Brunton estimated between 622 to 933 horses were shod by the two blacksmiths who worked on the Kilmanagh Crossroads property between the 1850s to 1890s (ASI 2013:33).

The presence of these seemingly unremarkable and commonplace horseshoe nails contributes to our understanding of the lives of rural blacksmiths in 19th-century Ontario.

By Janis Mitchell

References

ASI (Archaeological Services Inc.) 2013. Stage 4 Mitigative Excavation of the Kilmanagh Crossroads Site (AkGx-48) Dixie Road and Olde Baseline Road, Design for Road Improvements, Part of West Half Lot 34, Concession 4, Geographic Township of Chinguacousy, Town of Caledon, R.M. of Peel, Ontario. License Report on file with the Ministry of Citizenship and Multiculturalism, Toronto.

Brunton, Miranda. 2014. Power in Numbers: the Anthropological Implications of Horse Shoe Nails on Blacksmith Sites. Paper presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference in Québec City.

Ball, Donald B. 1999. Toward Advancing Nail Patterning Studies and structural Identification on Historical Archaeological Sites. Ohio Valley Historical Society 14(1999):1-22.

Doroszenko, Dena, and John Light. 1997. The Smithy, at Griffin’s Gables, Brockville, Ontario. In Home is Where the Hearth Is the Contributions of Small Sites to our Understanding of Ontario’s Past. Edited by John-Luc Pilon and Rachel Perkins, pp. 56 – 71. Ottawa Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society, Hull, Quebec.

Light, John D., and Henry Unglik. 1987. A Frontier Fur Trade Blacksmith Shop 1796 – 1812. National Historic Parks and Sites, Environment Canada – Parks, Ottawa, Ontario.