Various types of stone tools are recovered from Ontario’s archaeological sites each year. Some are formed so perfectly that we know what their intended use was, and others are shaped in such a way that we can pretty much date them to one of Ontario’s prehistoric periods. However there is a tool type that can often defy the question of usage and period of creation.

Say hello to the expedient tool.

Expedient tools are just that: crude waste flakes from tool-making production utilized for a specific task once, or a few times, then discarded like the plastic cutlery we use today or a rock picked up to drive tent pegs into the ground.

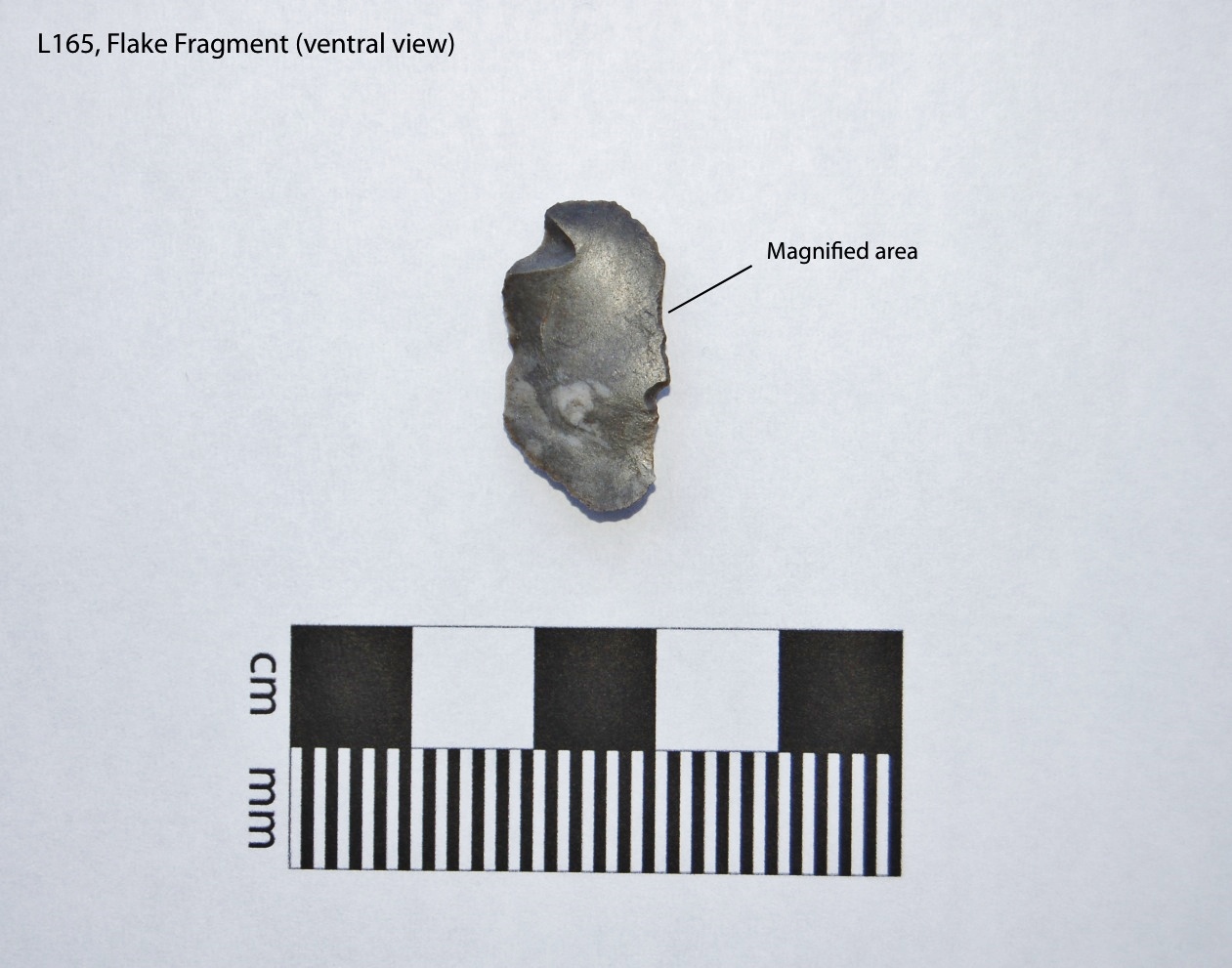

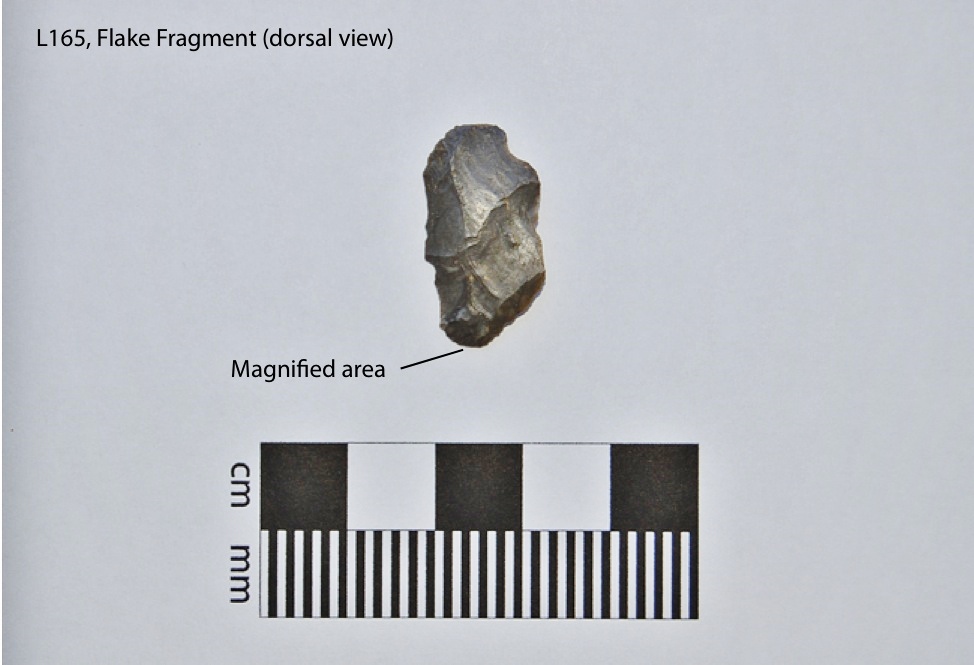

The example pictured, L165, made of Onondaga chert from South Niagara, comes from a little site east of Toronto. Without any “datable” formal tools found during excavations, we are left to ponder who may have used this site as a camp. L165 was but one of over 800 stone (lithic) artifacts recovered. Of that number, only 11 were deemed to be expedient tools.

L165 did not start out as an expedient tool. This artifact was created when someone using a deer antler or wood baton, struck it from a larger piece of Onondaga chert as they reduced it to produce a biface or projectile point. Whether L165 was created as a waste flake at the site or brought there from another camp we just don’t know. Someone liked the little flake fragment so much, they picked it up and used it — repurposed it if you like — as an expedient tool. L165 was lucky enough to be given a second life, one with purpose. Most of this stone debris, detritus, debitage is often left and forgotten as a waste byproduct of formal tool production.

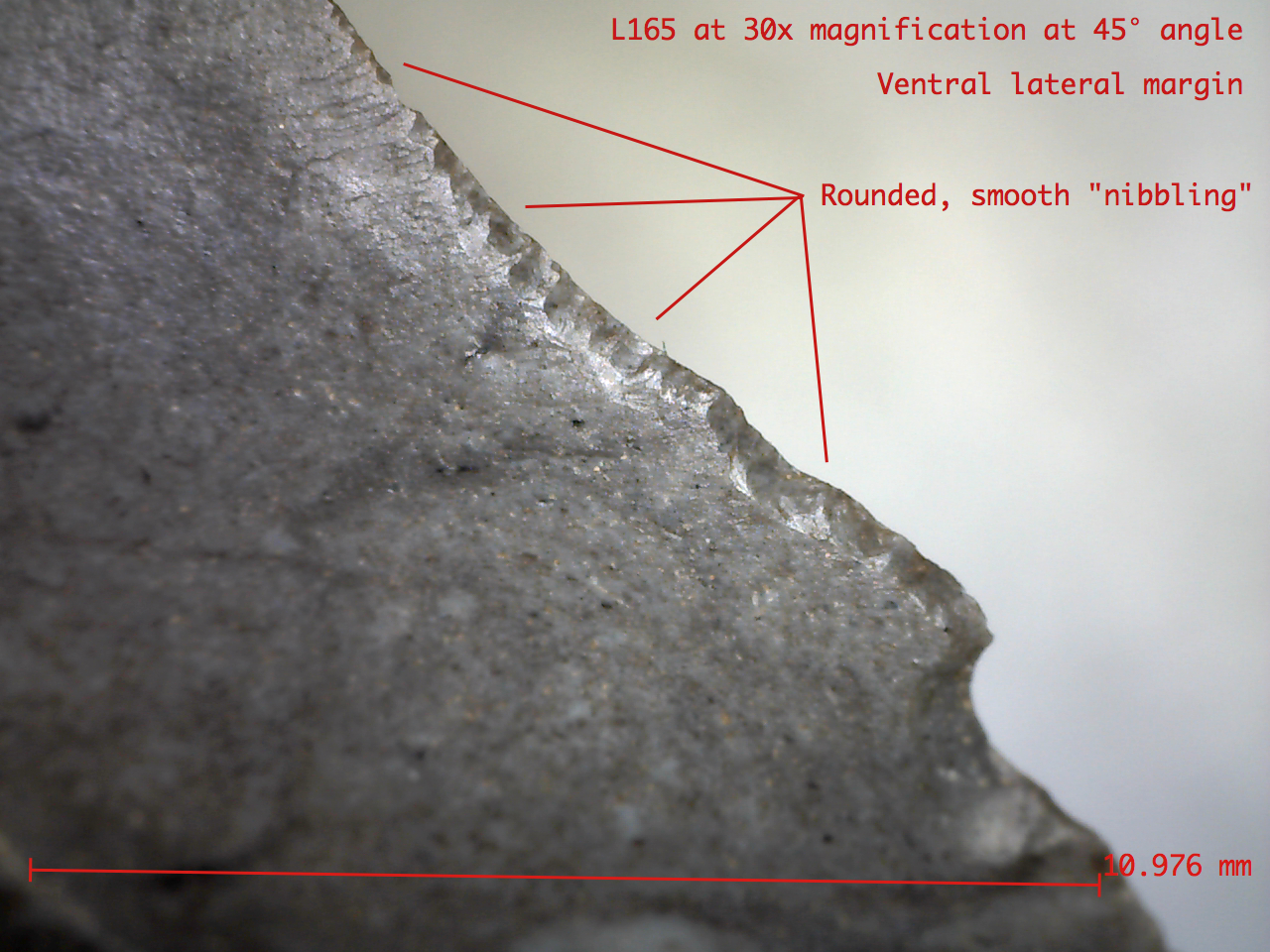

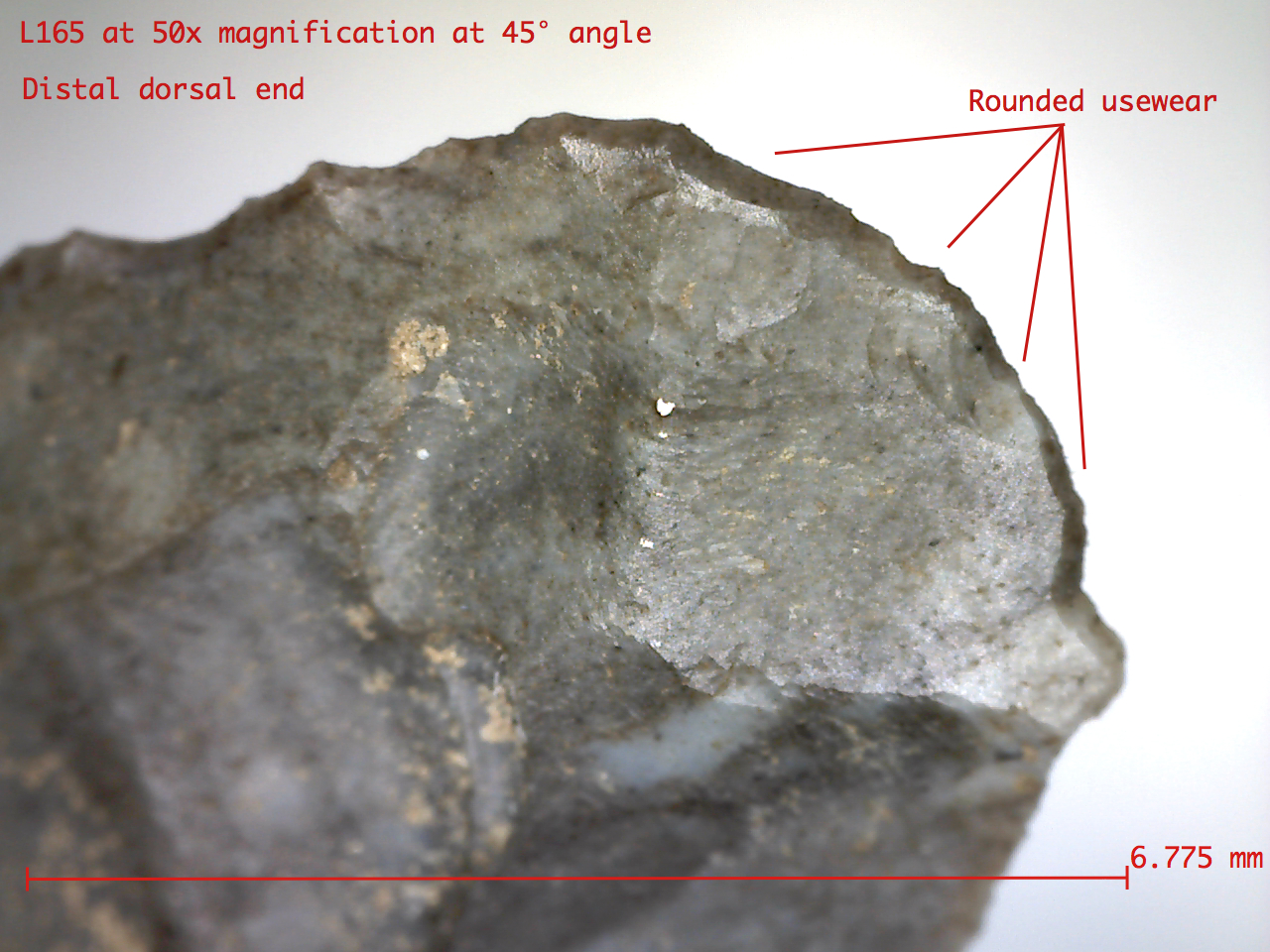

So, how can we be sure L165 is more than just a piece of detritus? By analyzing the little guy with a hand-held 10x magnifying glass we can see intentional “usewear” on two sides: the dorsal face and the ventral face. The usewear appears as a polished, rounded smooth dorsal end and on the ventral lateral margin as a wonderful series of rounded, worn micro flake removals — “nibbling,” if you like.

Lithic usewear analysts have completed exhaustive studies on usewear. Rounded, worn polish can often denote use on smooth materials such as wood, plants or animal hide but we will leave that for further pondering. Someone really liked L165. The evidence points to someone rubbing something with the tool’s distal dorsal end then maybe employing a shaving or scraping action with the ventral lateral margin. Detailed work perhaps?

We cannot crack every mystery associated with Ontario’s archaeological sites. It is artifacts like L165 that often, by their very ambiguous nature, fuel the imagination and let our thoughts run wild as we try to picture the people who camped in a little clearing east of Toronto that day long long ago, getting on with their daily lives. Lives where, for a moment perhaps, L165 played an important role before being dropped and forgotten a second time.