In honour of St. Patrick’s Day, we would like to present a few of our favourite Irish artifacts collected from various sites around Ontario. Enjoy!

The O’Connell Repeal Button

Recovered from the Holden site in Stouffville, this brass, looped-back button (Cat.#4047) is decorated with the image of Daniel O’Connell. An important figure in Irish history and national icon, Daniel O’Connell spearheaded grass-root political movements in support of Catholics’ rights and the Repeal of the Union (as is evinced by the motto on the obverse of the button). The Act of Union of 1801 eliminated an Irish parliament, reduced the number of Irish representatives, instituted duties on imported Irish grain, and brought other changes to the political and legal (as well and social and economic) relationship between England and Ireland, to Ireland’s detriment. As Foster (1988) notes, this was “a structural answer to the Irish problem, with overtones of ‘moral assimilation’ and expectations that an infusion of English manners would moderate sectarianism.” Charismatic and eloquent, O’Connell routinely commanded audiences—made of country folk—over several thousand.

After winning Catholic Emancipation, O’Connell turned his attention to repeal, founding The Repeal Association in 1840. Unfortunately, the Repeal Movement was quickly overshadowed by the events surrounding the Great Famine of 1845-1852, when over 2,000,000 of O’Connell’s support base (the so-called peasantry) perished from lack of food and associated diseases. However, during the first half of the 1840s, O’Connell and the Repeal Movement captivated the political scene and demonstrated that the oft-overlooked Irish farmer and labourer were vital to the political process. The evidence of this involvement is epitomized by the transformation of an everyday button into a badge of subversive political affiliation. While the obverse of the button would have been visible to others, the reverse slogan of the button was for the knowledge of the wearer alone. This slogan reads “IRELAND AS SHE OUGHT TO BE” and was a common phrase in the political rhetoric of the day. It is likely part of a longer verse, which is as follows:

[quote title=”IRELAND” Text=”Ireland as She ought to be,

Great, glorious and Free;

First flower of the earth,

And first gem of the sea.

” name=”Irish Verse” name_sub=”Unknown Author”]

The button may have been purchased at an O’Connell mass meeting in Ireland, which often carried a fair-like atmosphere and attracted salespeople and peddlers; however, this is not necessarily the only place where such a “mass consumption” item may have been available. Certainly the button may have had functional meaning only—it was simply a button. However, with the clear political message of the button, as well as the connection between Ireland and Ontario in the 1800s, this is unlikely.

[distance1]

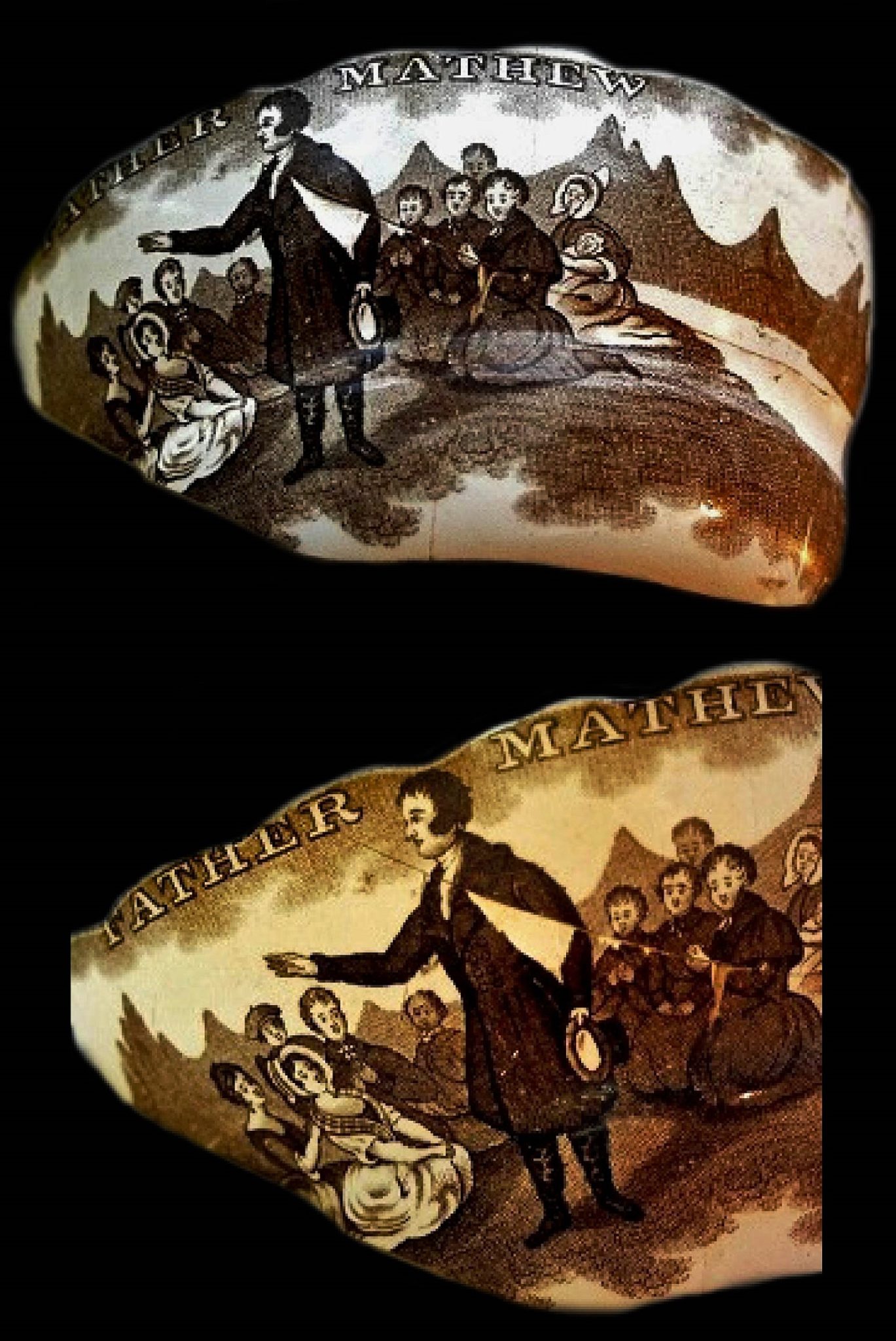

The Father Mathew “Waste” Bowl

This white earthenware waste or slop bowl was found among the remains of a mid-nineteenth century house at the corner of Bathurst and Adelaide in downtown Toronto. It was part of a tea set and cold tea was poured into it, before filling one’s cup again. It is decorated with the image of Father Theobold Mathew administering a temperance oath to a group of his followers. This exact image is also depicted on a teacup recovered from a site where Irish immigrants lived in the mid- to late-nineteenth-century known as the Five Points in New York City (Yamin 1998). The image depicts an acceptance of the Temperance Movement that preached that indulging in excess, intemperance, and immortality led to disease and melancholy.

Catholic temperance organizations were formed in the early-to-mid nineteenth century to offset the connection between Irish Catholics and alcohol. Some of the more popular temperance movements were inspired by the Irish priest Father Theobold Mathew, who at the request of the church travelled around the United States for two years to spread the word about abstaining from alcohol and other forms of immoral behaviour.

Stephan Brighton (2008) has interpreted the image on the Five Points teacup as a symbol of Irish cultural identity and social conversion in the “struggle to become Irish-American citizens”. During that time, the American protestant community believed Irish Catholic immigrants were a “social plague” on society because of their use of alcohol. The idea was that there were two groups: the deserving poor and the undeserving poor, with the later labeled so because of their supposed intemperate and delinquent lifestyles. The fact that a waste bowl with the same image was discovered in Toronto speaks to the popularity and widespread knowledge of Father Mathew in North America.

[distance1]

The Irish Harp Brooch

This copper-alloy brooch was discovered at the Toronto General Hospital site, on King Street West in downtown Toronto. The Toronto General Hospital figured prominently in the history of Toronto as the place where many of the 100,000 Irish immigrants who landed spent time in the summer of 1847 (for more information, see Mark McGowan’s book Death or Canada: The Irish Famine Migration of Toronto, 1847, and see the film here).

The brooch shows an Irish Lady Harp, surrounded by an English Rose and a Scottish Thistle. This unison symbolizes a belief in Ireland belonging to a UK – one with England and Scotland. “Friendly societies” produced items like this so that members could display their support for such a movement.