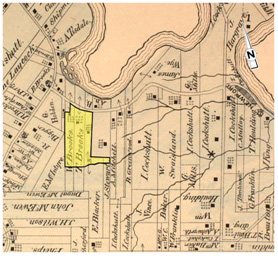

Stage 4 archaeological salvage excavations were carried out in the summer and fall of 2013 at the Blacker’s Brickworks site (AgHb-415) located within part of the area of proposed residential development at Tutela Heights Phase 1, Stewart & Ruggles Tract, formerly, County of Brant, Ontario. Operational circa 1870-1890, the site was the smallest of four brickyards in the City of Brantford and surrounding Brant Township owned by Edward Blacker, and later his sons Robert and William.

The 2013 investigations extended over approximately 9,770 m2 and revealed evidence of large-scale filling and grading activities carried out to prepare the site as a brickyard, more discontinuous remains of the brick-making process, and finally another massive round of grading, filling and drainage manipulation to bring the site into agricultural production following the closure of the brickyard.

Preparation of the poorly drained site, which was located at the bottom of a bowl formed by surrounding ridges and hills, necessitated filling in natural creek channels, installing an elaborate system of box and tile drains, and excavation of a perimeter drainage/boundary ditch along the north and east sides of the site. This served to divert water into an open pond at the south end of the site, remnants of which remain today. The drainage system was maintained and modified throughout the life of the brickyard. Major earthmoving was also required to level and stabilize parts of the site area.

Direct evidence for brick production was variably preserved. An extensive length of a linear clay winning trench cut into a steep south-facing slope, just beyond the north boundary/drainage ditch was uncovered. The heavily disturbed and largely truncated remains of a circular feature in the central portion of the site may represent a draught-driven ring pit for tempering raw weathered clay.

The most obvious remains of the brick-making operations were the pavements for the bases of the “necks” or “benches” and floor channels of up to six individual clamps, along with areas of variable burning and soil alteration that represent the locations of at least two more clamps for which minimal or no structural remains survived. The complex stratigraphic relationships between some of these deposits indicate that they relate to at least two separate firing events. No complete footprint of any one clamp was preserved; the longest sections of foundation pavements to survive measured around 28′ (8.5 m) long and at least 18′ (5.5 m) wide. The clamp remains documented by the excavations undoubtedly represent only the last one or two seasons of production at the site, as the ground preparation that preceded the construction of these features would have removed evidence of the earlier structures. Given that the clamps largely sat on top of the potentially unstable fills laid down in the former creek channels, this was likely a process that had to be repeated frequently, perhaps even on a yearly basis. The upper fills of the creek channel were found to contain large quantities of fired soil and brick debris derived from demolished clamps.

Fewer than 270 (non-brick) artifacts were recovered during the excavations, almost all of which were derived from the massive fill deposits. This is, in part, a consequence of the brickworks being a seasonal industry of relatively short duration, but other taphonomic factors, not least of which was the post-abandonment earthworking, had their effects.

Architectural class items predominate the assemblage, a reflection of the many structures that would have been necessary for the operation, but for which little other evidence survived. There was also a relatively high proportion of kitchen- or food-related class artifacts, which undoubtedly relate to meals taken on site during the work day. Although the sample is exceedingly small in terms of numbers, it is interesting to note that most of the tablewares date to the circa 1800-1840 period, some 20-30 years before the development of the site. This may indicate use of “surplus” or “old fashioned” pieces that were no longer wanted at home, but were suitable for the rough and tumble of the work place. Tools and equipment class artifacts are surprisingly few, given the industrial function of the site and, with the exception of some pug mill blades, most would be found on any other type of rural nineteenth-century site. This is undoubtedly a reflection of the decommissioning process, wherein all serviceable tools, and most certainly the specialized equipment, was taken to one of the other brickyards operated by the Blackers.

Despite these limitations, the investigations at the Blacker’s Brickworks site have provided a rare insight into the local manufacture of bricks in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Only a handful of such sites have been subject to archaeological investigation in North America, let alone Canada or Ontario. Evidence not obtainable from documentary sources has been recovered and has increased our understanding of this process and its place in Ontario’s history.