For National Indigenous People’s Day, we are highlighting the artistry of beads that we have recovered from Indigenous archaeological sites and celebrating the innovative beading of contemporary Indigenous artists. After sharing the careful craftsmanship and manufacturing process of excavated beads, we will be profiling four inspiring Indigenous artists who are finding new meaning in their craft.

Indigenous beadwork often involves meticulous embroidery using colourful glass beads, which were first introduced to North America through European trade. From an archaeological perspective, the importance of beads in Indigenous cultures far predates European contact. On many Indigenous village sites that we have excavated in Ontario, we have recovered beautiful beads made of stone, shell, and bone. The cultural practices of making beads, creating jewelry and embroidering clothing spans back centuries, if not millennia.

Contemporary Indigenous artists are connecting to these older traditions. Barb Nahwegahbow, an Anishnaabe jeweler from Whitefish River First Nation, describes the relationship she feels to her craft:

“Our people have always been adorned with beautiful jewellery – even before the arrival of the European settlers/colonizers – whether it was made with shells, porcupine quills,… I love looking at old photos because I appreciate that adornment and it inspires me that our people were always so beautifully accessorized. I don’t seek to replicate that type of jewellery, but continue the tradition of making what I consider to be beautiful jewellery with earth’s bounty” – from the Anishninabek News , Dec 14th, 2015

Stone Beads in the archaeological record

Steatite, or soapstone, beads are found on village sites from the Late Woodland period, ranging from 1200 to 400 years ago. These beads range in colour from light pink-beige, grey-brown, to black. Beads are also sometimes made from hematite or siltstone, which are a striking red in colour.

At the Hidden Springs site, a late fifteenth-century Huron-Wendat village, we recovered 12 soapstone beads. Only one of these beads was complete or finished, giving us insight into the manufacturing process.

How to make a stone bead

First a bead was roughly shaped into a disc, and then the exterior surface was carefully rounded and smoothed. Soapstone is soft, so it can be shaped by rubbing it against sandstone or even loose sand in a piece of deerskin, which will smooth and polish it nicely. The initial shaping into a rough disk might have been done with another stone tool made from chert, such as a sharp flake.

Next, the beads were perforated, which was done by drilling from both sides until the hole met in the middle. We know that a pointed chert drill was used for this process, as beads often have telltale horizontal striations on the side of the perforation.

Looking at the perforation of a bead can also show us if the bead was heavily worn after it was made. Beads were strung on a piece of leather or cord, which over time polished and wore away the centre, until the hole slowly acquired an oval shape.

On the sites that we have excavated, round discoidal shaped beads are the most common. But beads come in many shapes and sizes. Long tubular beads and rectangular beads are also found in Ontario.

The adaptability of Indigenous beading traditions

In the Collingwood area, many of the red siltstone beads found on Tionontaté sites from the first era of European contact bear a striking resemblance to European red glass trade beads. This may be an early example of Indigenous people adapting their beading traditions to the presence of new materials. Indigenous beading is an art form that has been transformed many times over the centuries and has proved itself infinitely adaptable to new materials and functions.

Beads serve as a vehicle for expression, identity, and creativity. Today, we see that many Indigenous artists are reclaiming traditional beading techniques to connect to their heritage, as well as using beadwork as a starting point to create new, exciting art pieces.

Artist spotlight

Samuel Thomas is a Cayuga beadwork artist who has used his art to explore the legacy of the residential school system in Canada.

In 2016 he traveled across the country to conduct group beading sessions with school survivors. Together they embellished six doors taken from residential schools with beautiful floral and botanical motifs. These pieces were displayed at the Niagara Falls Museum as part of their “Opening the Doors to Dialogue” Exhibit. Samuel describes his art as “striking reminders not only of the Indian residential school system legacy, but also of the beauty, strength, and resilience of the survivors themselves”

Samuel received recognition from the Canada Council for the Arts, you can read more about his work here: https://canadacouncil.ca/spotlight/2017/01/opening-doors-to-reconciliation

Catherine Blackburn is a multi-disciplinary artist and jeweler from Saskatchewan of Dene and European ancestry. She brings together mixed media and fashion, using traditional beading techniques on modern garments.

In 2018, Catherine created a collection called “New Age Warriors” featuring futuristic plastic armour rooted in traditional beading methods and creating striking images of a future built by strong Indigenous women.

https://www.instagram.com/catherinebjewellery/?hl=en

https://www.catherineblackburn.com/new-age-warriors

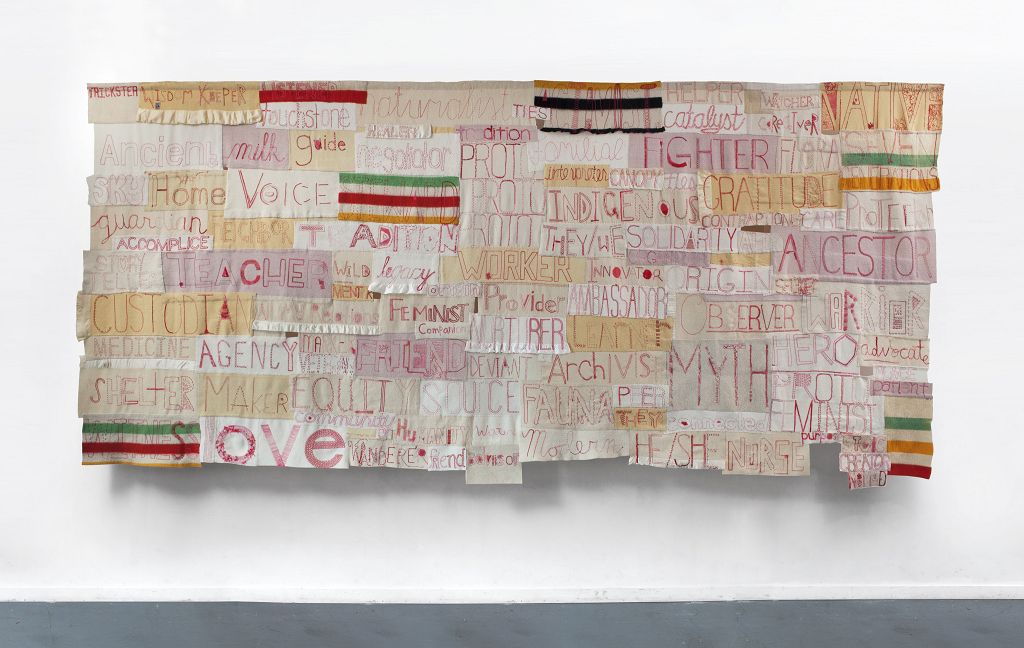

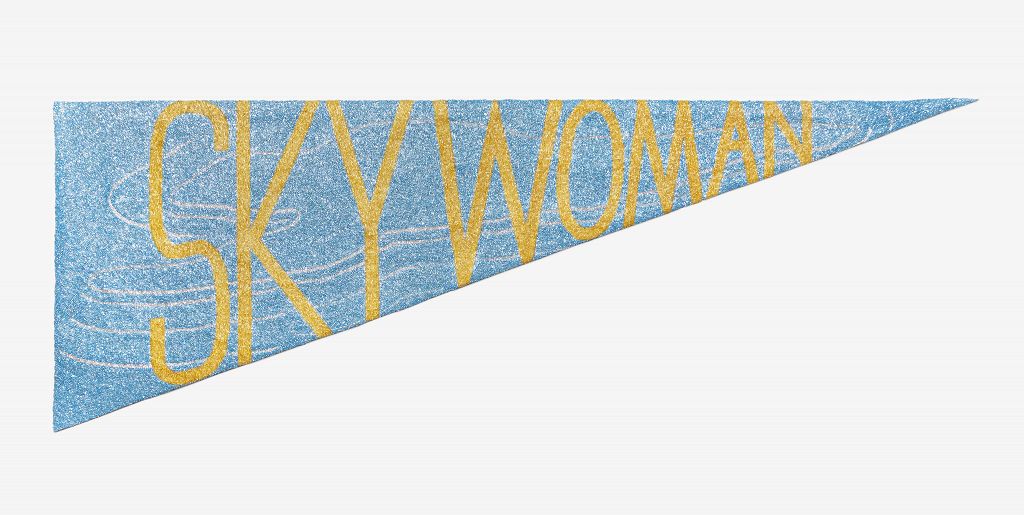

Marie Watt is a multidisciplinary American artist and citizen of the Seneca Nation who pulls heavily from Iroquois history, Indigenous teachings, and the importance of community in her work. To create some of her large-scale artwork she has organized large volunteer sewing circles who bead and embroider banners and textile pieces. In 2017, over 200 participants helped her create a banner “Companion Species” for an exhibit at the Northwestern University’s Museum of Art.

https://www.mariewattstudio.com/

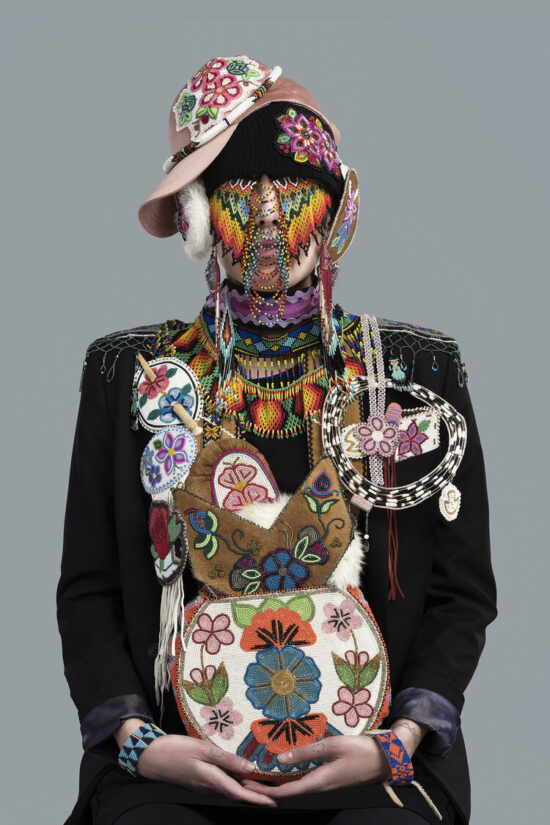

Dana Claxton is a film, video, photography, and performance artist working out of Vancouver and member of the Lakota First Nations located in Saskatchewan. In her 2018-2019 Series “Headdress” Dana photographed five women draped in the beadwork from their personal collections and cultural backgrounds. Dana’s work celebrates Indigenous cultural abundance and beauty.

National Indigenous People’s Day is a perfect opportunity to recognize the outstanding contributions of Indigenous artists, both today and in the past. Let us continue to celebrate their stories, their innovations, and the beauty of their artwork.

Written by Caitlin Coleman

References

Allaire, Christina.

“Meet 8 Indigenous Beaders Who Are Modernizing Their Craft.” in Vogue, April 24, 2019.

https://www.vogue.com/vogueworld/article/indigenous-beadwork-instagram-artists-jewelry-accessories

ASI

The Archaeology of the Hidden Spring Site. (AlGu-368)

June 2010.

Blackburn, Catherine.

Artist Bio, 2021.

https://www.catherineblackburn.com/untitled-c24vq

Claxton, Danielle.

Bio and CV, 2021

https://www.danaclaxton.com/about

Fox, William A.

“Miskwo Sinnee Munidominug.”

Archaeology of Eastern North America Issue 8, 1980, p. 88-90.

Niagara Falls Museum.

“Opening the Doors to Dialogue” Exhibition, May 11, 2019 – January 5, 2020.

https://niagarafallsmuseums.ca/exhibitions/current/opening-the-doors-to-dialogue

Smith, Christine.

“Indigenous and Ingenious brings out the talented.” in Anishninabek News, December 14, 2015.

http://anishinabeknews.ca/2015/12/14/indigenous-and-ingenious-brings-out-the-talented/