The Challenges of Curating Early Plastic Artifacts in Archaeological Collections

Earlier this fall we pulled a small archaeological collection out of our archive only to discover a minor disaster. An artifact made from an early form of plastic was beginning to decompose, releasing gas into the rest of the collection. The result was a fragmented artifact, partially melted archive-quality plastic bags, and bags and provenience cards whose recorded information had faded to an almost illegible bright yellow.

Our problematic artifact was a faux tortoiseshell hair comb which was likely made from celluloid. Celluloid was the first synthetic polymer, created by treating cotton fiber with camphor. The comb was originally catalogued as a single artifact. When re-examined, all the tines had fragmented and the body of the comb was broken into three parts, resulting in 18 separate pieces of plastic.

Early plastics are inherently unstable materials, particularly in the case of archaeological objects which have been exposed to the elements. The issue of how to maintain plastic artifacts is becoming a huge problem for conservators in both the archaeology and modern art worlds. There is a growing conversation about the breadth and depth of this problem, particularly in the case of composite objects.

The goal of early plastics was to imitate beautiful, but expensive natural materials like ivory, horn, shell and in our case tortoise shell. Plastic, as a new material, helped democratize the ownership of beautiful things. Wearing a real tortoiseshell hair comb was a luxury reserved for the upper classes, but with the invention of plastic women from many different income brackets were able to wear the same fashions. At the turn of the century the plastics revolution was just getting started, with a huge boom in new consumer goods just on the horizon.

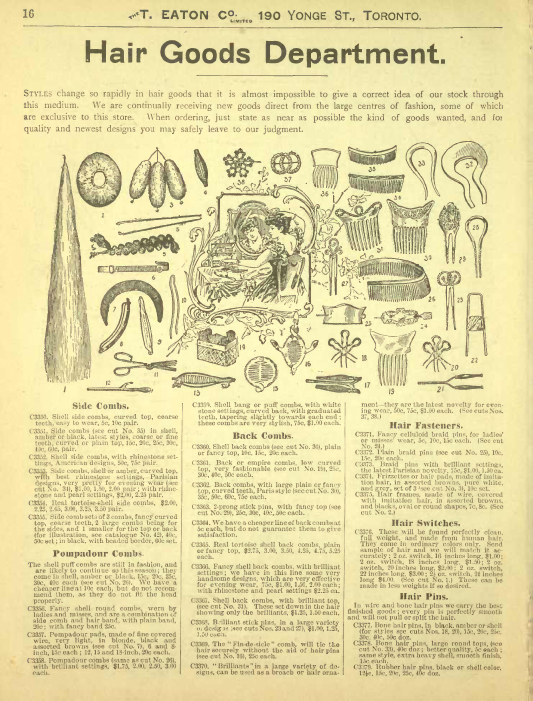

On this page of “hair goods” from the 1899-1900 Eaton’s Catalogue, we can see this democratization in action. Many styles of hair tools were available at different price points, with cellulose and authentic tortoiseshell combs being sold side by side. Despite the challenges of conservation, these early plastic artifacts are an important hallmark of consumer life at the turn of the twentieth century.

Due to the poor quality of our comb and the effect it was having on the collection around it, we made the difficult decision to document and discard this artifact. This comb was part of a Stage 2 test pitting and surface collection project in downtown Toronto, for an area that proved to be disturbed, and not considered an archaeological site. All the other artifacts from this collection were rebagged and given fresh cards with clear writing.

We have had a few key takeaways from this experience:

First: early plastics are incredibly volatile, and collections with significant plastic artifacts need to be carefully monitored. Plastic artifacts should be kept separately from the rest of the collection (especially metals) and kept in a cold, dry environment to slow the deterioration of the cellulose esters. They should also be kept well ventilated and/or kept with acid scavengers which absorb the acetic acid that is off gassed as the esters decay.

Second: once artifacts have deteriorated to this extent, the priority is to protect the rest of the collection over retaining a toxic artifact.

Third: we are more likely to miss an artifact problem in a small, archived collection that is not being actively worked on. The lab is actively pursuing getting these small collections into a repository at the Museum of Ontario Archaeology, where they can be more carefully monitored.

Written by Caitlin Coleman and Kaitlyn McMullen

References

Canadian Conservation Institute.

“Care of Objects Made from Rubber and Plastic” in Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 15/1.

https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/care-rubber-plastic.html

Hainschwang, Thomas and Laurence Leggio.

“The Characterization of Tortoise Shell and its Imitations.”

Gems and Gemology, vol 42, no. 1, Spring 2006.

Science History Institute.

“Science Matters: The Case of Plastics.” Published online on the sciencehistory.org website

https://www.sciencehistory.org/the-history-and-future-of-plastics

Westmont, V. Camille.

“Faux materials and aspirational identity: Celluloid combs and working class dreams in the Pennsylvania anthracite region.”

Journal of Material Culture, 2019, p.1-15